Toward Federal–State Regional Institutions for Security and Economic Renewal

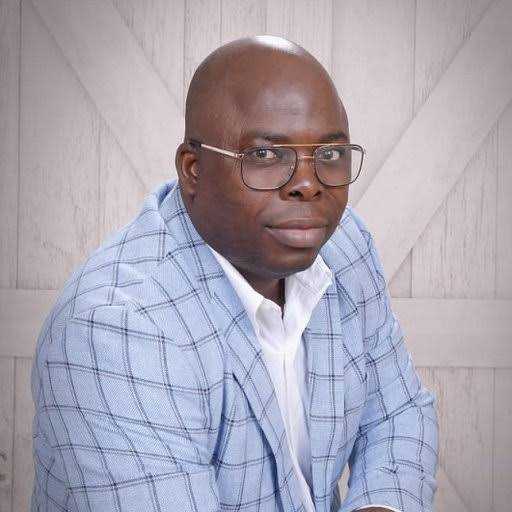

By Olarinre Salako

November 11, 2025

Introduction

President Tinubu’s declaration of a nationwide security emergency is one of the most consequential decisions of the Fourth Republic.

A country besieged by banditry, insurgency, kidnapping, violence, and illegal mining requires urgent action.

The President rightly called for “all hands on deck.” Yet some immediate steps need scrutiny. He announced: “I have asked the National Assembly to look into the matter of state policing so that states that are ready can begin to establish their own police services.” Combined with the sweeping withdrawal of police from VIP protection and reliance on mass recruitment, this signals intent but risks treating a structural crisis as a manpower problem.

Structural crises cannot be repaired with reactive adjustments. Nigeria needs a deliberate reorganisation of policing, linked with infrastructural development, at a level capable of strengthening national security.

That level is the regional—anchored on jointly owned federal–state Regional Development Commissions and a constitutionally empowered Regional Police Service working alongside the Nigeria Police Force.

Limits of Nigeria’s Centralised Police

Nigeria’s policing crisis is structural. With roughly 371,800 officers for nearly 230 million citizens, the police–population ratio stands at about 1:637 and closer to 1:1,000 once VIP deployments are considered, far below the UN benchmark of 1:450.

This is no longer a manpower gap, but a structural overload no single national command can credibly manage.

The withdrawal of VIP police details—now underway to redirect officers to frontline primary duty—must be handled with care. With the 2027 election cycle unfolding, this risks inadvertently exposing political opposition to danger. The unresolved assassinations of Bola Ige, Funsho Williams, Harry Marshall and others remain important warnings.

Security-exposed persons would be pushed toward engaging private, unregulated armed escorts and militia-style protection, creating a dangerous marketplace of force.

More fundamentally, recruiting “30,000 officers annually” cannot fix the basic mismatch between one national command and a federation spread across 923,000 km².

No major federal republic polices such size and diversity from its capital. Indonesia—with 279 million people—comes closest, yet operates with a better officer–citizen ratio of about 1:498, stronger provincial policing and better logistics.

Nigeria faces higher violence and weaker infrastructure while attempting a similar model with fewer officers.

Decentralisation is unavoidable; the question is at what level.

Why State Police Is Infeasible

Nigeria’s 36 states were not organically evolved federating units. They were created by military decrees and designed to depend on the centre. A genuine state police service would require state-level prisons, forensic laboratories, investigative bureaus, training academies, command systems among others.

Most states already struggle with existing responsibilities on the residual and concurrent lists. None can sustain additional function.

Two decades of democratic practice show persistent executive overreach. Governors routinely ignore constitutional limits—controlling LGA funds despite Supreme Court rulings, turning state electoral commissions into coronation platforms, and dragging entire assemblies with them during defections.

In such an environment, handing governors armed coercive forces would be dangerous.

Fiscally, many states struggle to pay salaries and pensions, maintain courts, fund capital projects or implement frameworks such as the Electricity Act 2023. Adding a stand-alone state police service—with its facilities and logistics—would overwhelm their finances.

The refusal to honour the Supreme Court ruling on LGA autonomy is itself a symptom of deep structural and fiscal fragility.

Nigeria needs decentralised policing—but not at the state level as currently constituted.

Regional Policing: A Balanced Middle Ground

Between an overstretched federal police and states that are structurally, politically, and fiscally unprepared for full coercive control lies a practical, historically grounded alternative: Regional Policing anchored on regional development.

Nigeria’s original federating units—the Northern, Western, Eastern, and later Mid-West Regions—emerged through the Richards (1946), Macpherson (1951), Independence (1960), and Republican (1963) Constitutions. They evolved from shared economic geography and socio-cultural cohesion, and for two decades (1946-1966) sustained effective civil services, courts, development agencies and internal security.

The current six geopolitical zones reflect these earlier regional blocs.

A Regional Police Service would diffuse authority across several governors, preventing the coercive dominance that 36 separate state commands could invite. It would standardise recruitment, training, and discipline, avoiding the fragmentation that state-level policing would produce.

Its operations would align with Nigeria’s real security geography—forest belts, banditry corridors, riverine and pipeline terrains, insurgency-affected zones, and areas of separatism-linked criminality. And it would institutionalise regional joint operations and shared intelligence against criminal networks that routinely cross state lines but operate within identifiable regional corridors.

Nigerians already instinctively organise regionally: Amotekun in the Southwest States, Hisbah in parts of the North, and the Civilian JTF in the Northeast.

What these efforts lack is constitutional authority and formal integration with the national police. A Regional Police Service would provide that coherence.

The federal push for forest guards underscores the need for terrain-specific security.

And because Nigeria’s security pressures are intertwined with land use, illegal mining, environmental stress and economic geography, regional policing must be integrated with regional development.

The Interlink between Security and Development

Nigeria’s insecurity grows from developmental failure as much as policing gaps.

Collapsed rural roads and deteriorating urban networks slow response times and cut off vulnerable communities.

Chronic electricity shortages suffocate industrialisation, close small businesses and expand the pool of unemployed youths open to criminal recruitment.

Illegal mining is not just economic sabotage; it finances armed groups and banditry that overwhelm federal policing.

Desertification, open grazing and expanding agricultural frontiers—fuel recurring clashes between communities and herders.

The creation of the Ministry of Livestock Development and emphasis on ranching acknowledges that security is inseparable from economic planning, land use, and regional infrastructure.

This is where the Regional Development Commissions (RDCs) should become indispensable. With mandates covering multiple states within each geopolitical zone, RDCs are uniquely positioned to coordinate the systems that shape both security and prosperity.

Properly empowered, RDCs can pool regional security and development financing; harmonise electricity planning under the Electricity Act 2023; regulate and secure mining corridors; plan inter-state transport, rail and logistics networks; and host critical security infrastructure no state can afford alone.

Regional Policing and Regional Development are two sides of the same coin. Security requires functional roads, reliable power, communications and economic opportunity. Development requires safety, predictability and the suppression of predatory criminal networks.

The regional tier is the natural scale at which these systems can be coordinated.

Yet RDCs are currently constrained by design. They were created as federal agencies with Acts of the National Assembly, not as genuine federal–state regional institutions domesticated in the states within their respective regional coverage.

Without real state co-ownership and alignment, they risk becoming mini-federal ministries—duplicative, under-funded and disconnected from the state governments whose cooperation is essential.

If RDCs are to drive regional development, they must anchor regional policing, and to do so, their institutional architecture must be redefined.

Constitutional Framework

Implementing Regional Policing requires jointly owned Regional Development Commissions whose redefined enabling Acts make them co-owned by federal and state governments, co-funded through shared contributions, and co-governed through a regional security and development board.

That reform would create Nigeria’s first genuine federal–state regional institutions—capable of managing security, infrastructure and economic planning at the scale where these challenges naturally occur.

It would also begin a gradual constitutional shift toward functional regionalism that strengthens rather than fragments the Union.

Within this framework, Regional Policing would not stand alone. It would operate inside an integrated system of regional economic planning, inter-state railway and road transportation, mining regulation and shared security operations.

Essentially, a regionally operated concurrent legislative lists with oversights shared by the National Assembly and respective States Assemblies.

The path to such a system is clear. Governors in each zone should convene a Regional Security and Legislative Reform Conference, bringing together National Assembly members, Speakers of State Assemblies, RDC leadership, traditional rulers, civil society, and security experts.

A technical committee of lawyers and policy experts would draft a harmonised Regional Police Service Bill.

Each governor would then transmit the same bill to his State Assembly for coordinated passage across the zone—a difficult but not impossible feat when national survival is at stake.

In parallel, the President and federal lawmakers would pursue amendments to the Constitution, the Police Act, and the RDC Acts to anchor the system in national law.

The resulting structure—a unified Regional Police Service Law, a Regional Security and Development Board, a transparent funding framework, and a professional regional command working with the Nigerian Police Force, Department of State Services, and Nigeria Security and Civil Defence Corps—would deliver decentralised security without disorder and regional responsiveness without secessionist drift.

Conclusion

Regional Policing—anchored on joint federal–state Regional Development Commissions—is more than a security proposal.

It is a blueprint for renewing the Nigerian federation.

It aligns with political realities, reinforces national cohesion, deepens interstate cooperation.

If implemented with clarity and discipline, it will reshape how Nigeria organises public safety, manages development and governs its vast territory.

It offers decentralisation without fragmentation, reform without recklessness and federalism without weakening the Union.

Regional Policing anchored on regional development is the most credible path toward a safer, stronger and more economically integrated Nigeria.

Olarinre Salako, Ph.D., an Oyo born Nigerian-American, writes from Texas USA. He could be reached via email: olarinre.salako@gmail.com